Exploring the intricate chambers of Tutankhamun’s tomb is an enthralling journey, as archaeologists unravel the layers of mystery surrounding the ancient pharaoh’s final resting place.

This story began with the death of a teenager – the ruler of Ancient Egypt. His name could have been lost to oblivion if not for a series of mysterious deaths, astonishingly linked to him. Tutankhamun was not an outstanding king, but events that unfolded 3000 years later made him the most famous pharaoh who ever lived.

Tutankhamun’s reign falls within the period of the New Kingdom – the zenith of ancient Egypt. He was the last representative of the 18th dynasty, ruling for a short time, presumably from 1332 to 1323 BCE. The pharaoh died at the age of 19 or 18 and was buried in the Valley of the Kings.

Tutankhamun is believed to be the son of Akhenaten, the famous pharaoh-reformer. The Egyptian throne passed to Tutankhamun when he was nine years old. As a result, during his rule, the fate of the country was more influenced by the former associates of Akhenaten than the young ruler himself.

The previous pharaoh authored a religious reform that shook the foundations of ancient society, replacing polytheism with a monotheistic religion, worshiping the sun god Aten, and eventually the pharaoh himself. Tutankhamun decided to return to the old gods. Akhenaten’s name was condemned, and his former capital, Akhetaton, was completely destroyed.

Debates about the cause of Tutankhamun’s death persist to this day. Archaeological evidence shows he was a frail and unhealthy youth. His body proportions were far from perfect, particularly with overly long arms. Hence, one of the most popular theories is a presumed serious illness. Some researchers vehemently disagree, insisting that the Egyptian ruler was entirely healthy. According to some recent studies, the pharaoh died from the wheels of a chariot – a trace of the wheel remained on the left side of his body. Whatever the case, one thing can be said with certainty: Tutankhamun died in his early youth and was buried according to all traditions.

The remarkable discovery by Howard Carter The discovery that shook the entire scientific world was made by archaeologist Howard Carter and his colleague Lord Carnarvon. The latter was not a professional archaeologist but funded a significant portion of the excavations that began in 1914. In those days, modern archaeological tools did not exist, so scientists had to work in very challenging conditions – long and often fruitless work. By 1922, Lord Carnarvon had become disillusioned with his endeavors and had stopped allocating funds.

<

At that time, Carter was excavating in the Valley of the Kings and, on November 4, accidentally discovered the entrance to a new tomb. The sealed door bore the symbol of royal blood – a sign of the burial of Egyptian nobility. Carter immediately informed Lord Carnarvon, who was in England at the time.

Before the opening of the tomb, an apparently unremarkable incident occurred with Carter. During his excavations, he was accompanied by a pet canary. One day, a cobra entered the scientist’s dwelling and ate the bird. Carter paid no attention to it, but his local assistants perceived it as a sign of impending disaster. The cobra was one of the symbols of Egyptian pharaohs.

But let’s return to the discovered door. On November 24, Carnarvon and Carter decided to take a closer look at the strange find. They inserted a lamp through a drilled hole and, miraculously, saw the luxurious burial chamber of the pharaoh. Unfortunately, it became clear immediately that the archaeologists were not the first visitors to the tomb. Thieves had visited several times, but for some unknown reason, they were forced to flee each time. This seemed evident as everything inside was overturned, although the pharaoh’s treasures were still in place. Investigating the circumstances of the attempted robberies took the archaeologists some time as they waited for authorities’ permission to conduct work in the tomb.

Work began on February 16, 1923. Archaeologists found that the tomb consisted of four chambers, the main one containing the mummy of the pharaoh. In the tomb, scientists found numerous gold ornaments, weapons, utensils, figurines, and symbols of royal power. Subsequently, two more bodies were discovered among the contents of the tomb, belonging to stillborn daughters of the pharaoh.

The Mysterious Death

The news of an archaeological sensation shook the entire scientific world. Understandably so, as it was about one of the most remarkable discoveries in the entire history of Ancient Egypt research! Howard Carter could hardly have imagined back then that the tomb of Tutankhamun would soon bring him even greater fame. However, such fame is not something anyone would wish for.

©Wikimedia Commons ©Wikimedia Commons

In the spring of the same year, another “insignificant event” occurred with Carnarvon: he was bitten by a mosquito. After a few days, Lord cut himself at the bite site, and soon noticed that a small scratch was suspiciously slow to heal. Carnarvon’s fears were justified when he developed a fever and soon passed away. It was then rumored that the mosquito that bit Lord was “poisonous.” The mystery of the story was heightened by the fact that at the moment of Lord’s death, the lights in Cairo suddenly went out. The cause of the blackout was never determined, but that wasn’t the only mysterious coincidence. Around the same time Carnarvon’s heart stopped, his dog, who was at his home in England, also died. Of course, all of this could be explained as ordinary coincidences exaggerated by the yellow press. However, Lord’s death and everything associated with it was just the first link in a chain of ominous events.

Lord Carnarvon died on April 5, 1923, four months after visiting Tutankhamun’s tomb. A few days later, Arthur Mace, one of the archaeologists on Carter’s expedition, also died. It appeared that Mace’s cause of death was poisoning. Upon returning to England, another specialist from those excavations, radiologist Archibald Reid, also died. George Gould, the American financier who observed the tomb excavations, died half a year later, succumbing to a fever.

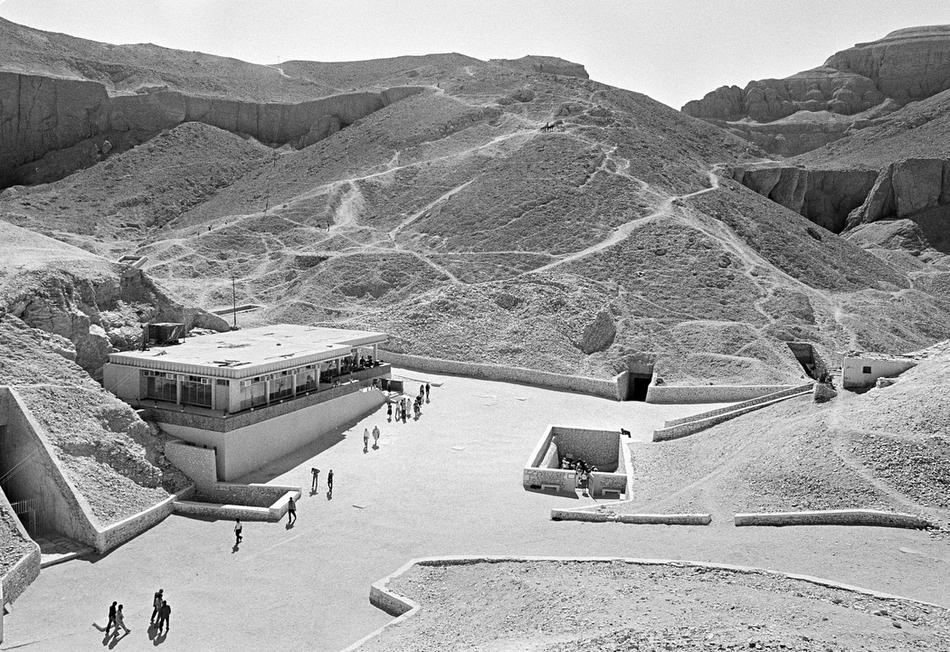

Entrance to Tutankhamun’s tomb (center) lies in front of the tourist center in the Egyptian Valley of the Pharaohs / ©Wikimedia Commons Entrance to Tutankhamun’s tomb (center) lies in front of the tourist center in the Egyptian Valley of the Pharaohs / ©Wikimedia Commons

Lord Carnarvon’s wife died from an insect bite, and his stepbrother soon took his own life. Finally, in 1928, Howard Carter’s young secretary, Richard Bartle, died. His death resulted from a heart failure, although Bartle had not complained about his health. All these people were involved in the study of the pharaoh’s mummy. In addition, victims of the “curse” included Professor La Fleur, X-ray specialist Reed, and several other scientists. In total, at different times, 22 to 25 people, in one way or another connected to the burial of the Egyptian pharaoh, died. It seemed as if Tutankhamun’s vengeance would reach anyone who dared disturb his peace…

Nevertheless, supporters of the esoteric approach sometimes overlook one important point: the main target of the “pharaoh’s curse,” archaeologist Howard Carter, died of natural causes in 1939. At that time, he was 65 years old.

In 1980, an interview with Richard Adamson, the last living researcher from Carter’s expedition, was published. Adamson also firmly rejected the myth of the curse of the Egyptian king. Strictly speaking, almost all deceased scientists at the time of their death were in very advanced age. Participants in Carter’s expedition lived on average for 74 years.

Archaeologists excavating ancient artifacts during digs in Cairo / ©Alamy Archaeologists excavating ancient artifacts during digs in Cairo / ©Alamy

However, not infrequently, not only deceased scientists but also ordinary tourists are attributed to the account of the Egyptian ruler. Cases of unexplained deaths continue even in our time.

The Origins of the Legend

First, let’s try to understand where the myth of the curse came from. It may sound strange, but the myth itself is nothing more than a newspaper hoax. Trying to ensure peace for the deceased, ancient Egyptians indeed resorted to various spells and incantations. According to modern specialists, hieroglyphs contain some warnings, but often they are interpreted too literally. Some warnings caution an unfortunate traveler against defiling the tomb or prohibit the visit to the tomb for a person with a bad reputation. In the case of Tutankhamun, researchers have determined that there is a spell here, protecting the rest of the Egyptian king and shielding him from the sands of the desert.

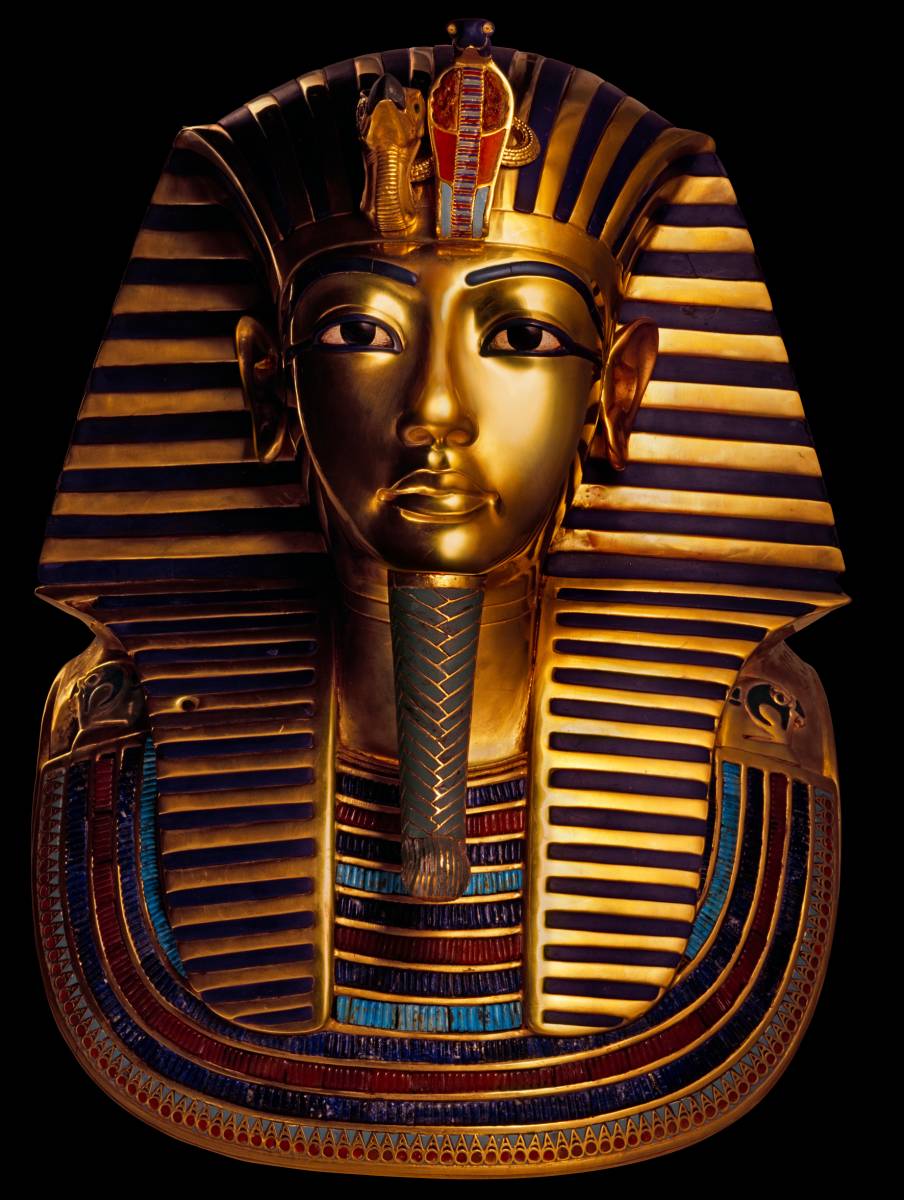

The face of Tutankhamun’s mummy / ©Getty Images The face of Tutankhamun’s mummy / ©Getty Images

The author of the curse of Tutankhamun was one of the journalists from the Daily Express. The writer Marie Corelli, the author of numerous works on mysticism, also contributed to it. After Carnarvon’s death, Marie Corelli and Arthur Conan Doyle (also a big fan of mysticism) claimed that they had warned the hapless archaeologists. Even earlier, British writer Jane Loudon Webb addressed similar themes. Her mystical work “The Mummy” was published in 1828. Later, authors of fiction continued to exploit supposedly terrifying warnings. This is how the ominous mystical image of Egyptian pharaohs formed in the mass consciousness.

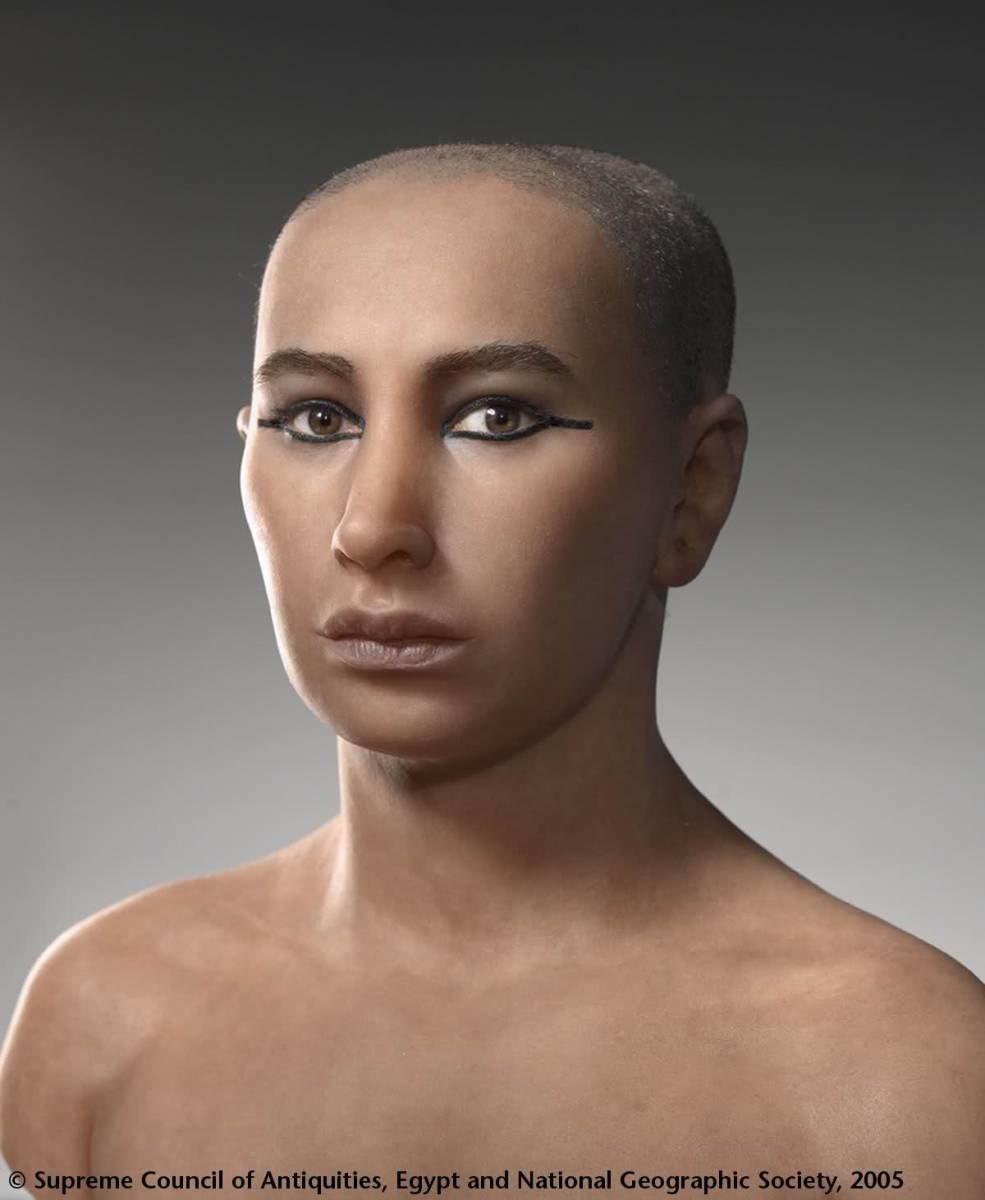

Reconstructed image of Tutankhamun. Reconstructed by French scientists based on facial reconstruction data obtained through computer scanning of the pharaoh’s mummy / ©National Geographic Reconstructed image of Tutankhamun. Reconstructed by French scientists based on facial reconstruction data obtained through computer scanning of the pharaoh’s mummy / ©National Geographic

“The Curse of Pharaoh Tutankhamun” made ancient Egyptian themes one of the most popular mystical directions in mass culture. One of the latest artistic works on this subject was the fantasy film “Tutankhamun: The Curse of the Tomb,” released in 2006.

The Invisible Killer

Nevertheless, the “curse of the pharaoh” could indeed exist, and it can be explained by entirely natural factors.

Initially, none of the participants in Carter’s expedition paid attention to the strange deposit on the walls of the burial chamber. Contrary to the initial version of cracked paint, the cause of the wall stains was a fungus. Thirty years after the series of mysterious deaths, the medic Geoffrey Dean noticed that the symptoms of the disease in scientists who visited the tomb resembled the so-called “cave disease.” Its cause is microscopic fungi. It’s clear that damp and dark spaces, like Tutankhamun’s burial chamber, became a favorable environment for their spread. Later, Egyptian biologist Ezzeddin Taha confirmed the validity of this assumption, discovering the fungus in the bodies of many archaeologists engaged in the study of Ancient Egypt.

In our era, antibiotics render the danger of such microorganisms negligible. However, if a person’s immunity is weakened, fungal infection can have quite severe consequences. In the 1990s, scientists took samples of secretions from the lungs of a tourist who died after visiting Tutankhamun’s tomb. It was found that the body of the deceased contained a fungus, which could have been the cause of her death.

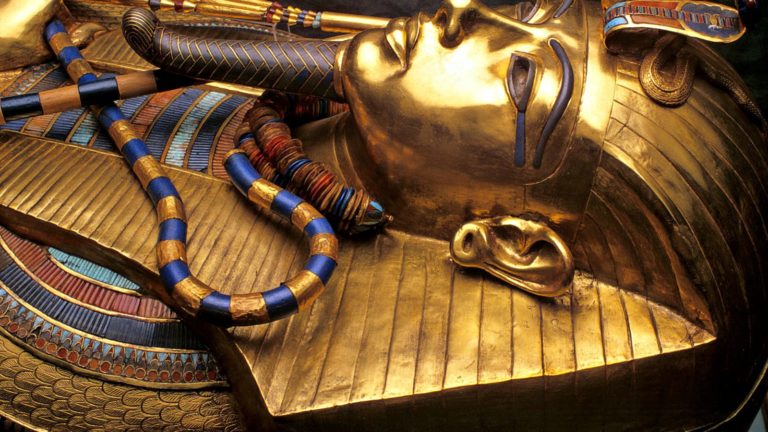

Sarcophagus of Tutankhamun being placed back into the underground tomb (Valley of the Pharaohs, November 4, 2007). The mummy of the 19-year-old pharaoh, whose life and death had intrigued people for almost a century, was placed in a special glass case with climate control, leaving only the face and legs uncovered / ©Wikimedia Commons

Members of Carter’s expedition could also have fallen victim to harmful microorganisms they contracted while being close to the mummy. One important circumstance supports this version. After 3000 years, the oils used for mummification had turned into glue. To extract the pharaoh from the tomb, Carter took a decisive step – he cut the mummy. In those years, Egyptologists rarely used special protective measures, and when in contact with the mummy, harmful microorganisms could easily enter the respiratory tract, causing severe illnesses.

Tutankhamun belonged to the XVIII dynasty of pharaohs – one of the most famous in the history of Ancient Egypt. Its reign dates back to the New Kingdom era. The founder of the dynasty, Ahmose I, united the scattered territories of Egypt, and his descendants ruled the country from 1550 to 1292 BCE. Several powerful rulers who changed the history of their country, as well as a number of female pharaohs, were representatives of this dynasty.

Modern researchers note that working with a mummy can be dangerous because a mummified body may contain harmful bacteria. There is also a reverse side to the issue: external bacteria can destroy the mummy.

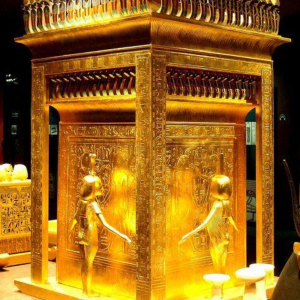

Ark of Tutankhamun. It housed vessels with his internal organs. Adorned with cobras and statues of goddesses: Isis, Nephthys, Neith, and Selket / ©Flickr

In our view, the version that the cause of death for visitors to Tutankhamun’s tomb was a fungus sounds quite plausible. However, there is still no official viewpoint regarding the series of mysterious deaths. There is also no evidence that harmful microorganisms killed scientists and ordinary tourists.

Tutankhamun’s father, Akhenaten, was one of the most prominent religious reformers in history. It was he who first introduced monotheism in Egypt, “abolishing” the entire pantheon of Egyptian deities and leaving only the Sun god Aten. Most likely, the aim of such innovation was to strengthen the pharaoh’s personal power. The reform could also have been used to centralize the Egyptian state.

To comment on this issue, we reached out to a current member of the International Association of Egyptologists, the president of the Association for the Study of Ancient Egypt, Victor Solkin.