From Doubt to Dominance: The Inspirational Journey of Russell Westbrook, Who Never Thought He Would Play in the NBA

Just 25 minutes south of Oklahoma City, on the border of peaceful Route 62, you’ll find Newcastle High School, which protrudes from the flat soil and buttresses itself abruptly, like an invasion of modernism. A man with luminous eyes is inside the gym, and he’s a firestorm. By any measure, he is not slim. Actually fashioned from marble. Strong and quick, he is. He captivates and frightens with his fabricated rage.

He clenches his jaw. A furrow forms on his forehead. His profanity is careless verse. You find yourself wondering if he’s indeed enjoying himself. In more ways than one, the annual Blue and White scrimmage that kicks off the Thunder’s training camp serves as a means of connecting with fans.

Every call is argued by Russell Westbrook Jr.

On October 4, 2015, at Newcastle High School in Newcastle, Oklahoma, Russell Westbrook (#0) and Nick Collison (#4) of the Oklahoma City Thunder showed their support during the annual Blue vs. White scrimmage during training camp. Important Notice for You

Getty Images/Layne Murdoch Jr.

Serge Ibaka, a power forward for the Thunder, is becoming more and more irritating to him. The Thunder’s pick-and-roll defense is completely out of practice since this is their first official game together since the end of the regular season.

According to Westbrook, “Man, we need to go small or something” in response to Serge’s foolish actions. How challenging is it?”

To soothe Westbrook, Durant places his big right hand on the nape of his neck. He frequently engages in this act.

Coach Darko Rajakovic’s assistant, who is on the white team, tries to reassure Westbrook.

Please tell me what you need from me.Rajakovic affirms. “Just tell me, tell me.”

There is no response from Westbrook.

Steps forward, Maurice Cheeks.

“What’s wrong?”With an air of casual ease, the Thunder assistant coach poses the question.

“No one’s pitching in!Westbrook begs. “If I cross over, someone needs to come and get me!” I’m going under because of that.

“However, you forfeited three going under,” Cheeks points out.

After giving it some thought, Westbrook finally says, “F–k it.”

He has himself re-enrolled.

Russell Westbrook when he first entered the NBA.

<Beginning his NBA career, Russell Westbrook.Getty Images

There is no way to damage Compton Avenue. Surely it is.

This frayed asphalt ribbon is beautiful. A cadence. A chronicle. It places unjust demands on people. The object is aware of discomfort.

Yet not every kind of suffering is bad. Sometimes it’s attached to a strange hope that only locals can understand.

Ultimately, this is a site of birth.

This is the hometown of Russell Westbrook.

This concrete is known to the child with the prominent cheekbones and chiseled jaw, who deals in an unusual combination of manufactured fury and form-fitting apparel. All this history, rhythm, and suffering is familiar to him.

At Barney’s, you may find his brand of sunglasses. The daringness of his Vine-inducing dunks is increasing. His enthusiasm baffles. Nobody could have foreseen his ascent to fаme and prominence on the hardwood. Yeah, not even he. To put it simply, none of it makes sense.

To begin, there is Compton Avenue. Another option is Jesse Owens Park. The living room of his parents’ modest apartment could also work.

“I never imagined I would be a part of the NBA,” remarks Westbrook. A large number of current NBA players have had talent since the age of eight. Up until the age of seventeen, I was terrible.

A hero’s backstory is unique to each superhero. Reluctance is a normal part of becoming a hero, but it should be met with ambition and determination.

There is a place for everyone. The one thing you can’t alter about yourself is your background. It’s an essential strand of DNA that’s as unbreakable as Compton Avenue. There is no end to its half-life.

Those who emerged from such a wasteland are neither diminished nor defined by the presence of steel-caged bооze stores, burning buildings, and streets that are constantly illuminated with flashing blue and red lights.

At other times, it’s simply home.

His transformation into the guy he is now was not an easy one, he admits. Los Angeles was my home growing up, so I learned that. My hometown is something I’m quite proud of.

The starting point of the excursion may be found by taking a left on 41st Street after swerving down Compton Avenue.

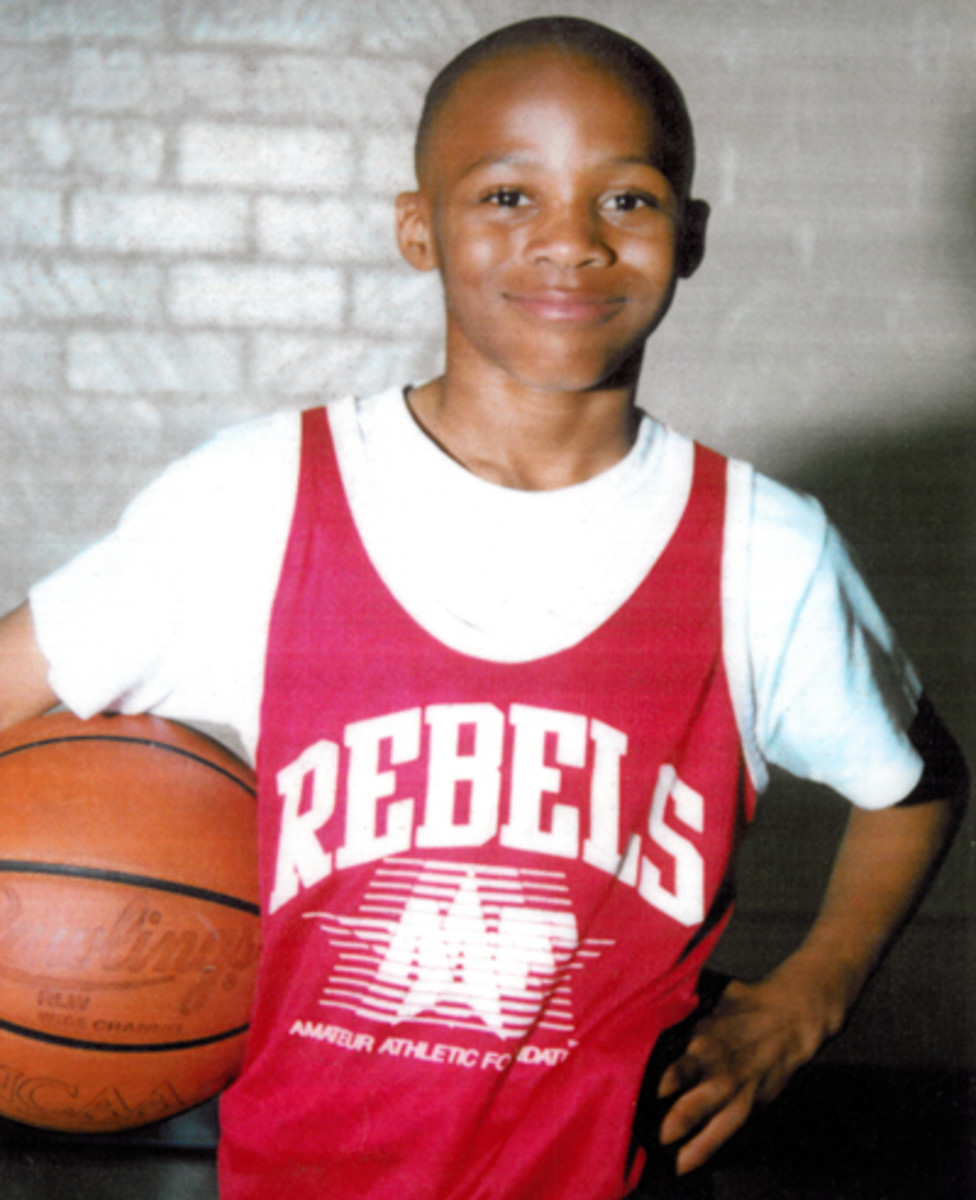

Russell Westbrook during his final year of high school at Leuzinger in Lawndale, California.

As a senior at Lawndale, California’s Leuzinger High School, Russell Westbrook (Getty Images)

Son Rises as Well

Ben Howland entered the former gym at Lawndale, California’s Leuzinger High School about 6:30 in the morning. Even though he had never seen Westbrook in person, the head basketball coach at UCLA was ecstatic. The players still hadn’t shown up, and the only other soul in the gym save Howland was a skinny kid scrubbing the floor.

Recruiting Westbrook wasn’t a top priority. Not at all one of the priceless McDonald’s All-Americans owned by Howland. His speed was known to him. Regarding his fervent defense. In his mind, Darren Collison, his freshman sensation, would benefit from having him as a backup. Pauley Pavilion’s student section would undoubtedly come to adore him.

Minutes after that, he was met by Reggie Morris, head coach of the Leuzinger. During their brief conversation, Morris gave him his word that he would be impressed by what he saw from Westbrook.

“Did Russell disappear?””What do you want?” Howland inquired.

“Just there,” Morris responded. The broom is being pushed.

Westbrook rounded up his teammates in the locker room after finishing the floor. He then gathered them together in a tight ball and started yelling at them like it was a jam-packed gym on game night. With his teammates close behind, Westbrook sprinted onto the court and immediately set up a layup line and other drills.

Howland recalls that Russell Westbrook was first introduced to him in a leadership capacity. “It was truly remarkable.”

Upon his return to campus, Howland approached Kerry Keating, the assistant coach at UCLA who had been instrumental in securing Westbrook’s recruiting.

“This kid isn’t fitted to play point guard,” Howland remarked.

Keating shot back, “I never said he was a point guard.” Got it. “I simply mentioned that he possessed the ability to play.”

The reality was that they were unaware of their possessions. In spite of this, they were aware of their feelings for him. His coworkers didn’t understand why Keating had been secretly watching him for a few years.

It wasn’t until UCLA assistant Donny Daniels watched Westbrook play in a high school tournament versus Westchester that he understood why. He forced the action after shooting two airballs, making bad decisions, and becoming irritated. Kids play like that when they’re on the verge of losing their scholarship opportunities.

“This kid can play.” That was Daniels’s only impression.

Almost every play of the game was impacted by his motor, passion, and competitiveness. When it came to defense, his length and speed gave him the upper hand. When he attempted to include other people, he made the majority of his mistakes. He surprised everyone with his jump shot’s rotation, lift, and release. Diving on the floor, he fell.

After a poor performance, “you don’t judge a kid,” Daniels cries out. He had so much untapped ability. Simply dumping the ball into the basket would do it. It was raw, man.

During Westbrook’s senior year, Keating witnessed him play six times, which was the maximum allowed by the NCAA at the time. It was easy for him to make sure his dad noticed him during games because no other scouts were there. He’d put up with terrible games that had hours of wait time.

Many questioned his decision to sign a 5’9″ guard without shooting ability.

According to what Keating remembers, “He was this rugrat who played like a bat out of Һell. He was like a crazed dog.”

The intense, professional pickup baller Westbrook’s father would take him to various gyms and parks around town to practice jump shots and drills that he had created, which greatly contributed to the development of his son’s frantic style.

“It was all work-ethic stuff,” recalls Jordan Hamilton, a fellow Compton native and former first-round draft pick. “They would do military drills.”

The need of hard effort was drilled into the boy’s head by having him perform sandbox agility drills, push-ups, sit-ups, continuous sprints, and other such exercises.

His dad always told him to “outwork them.”

On top of that, Westbrook wasn’t little; he was tiny. A quick spin to the side would make him vanish, and most people wouldn’t have seen any difference.

They had to work together to lift the boulder-sized chip and set it firmly on Russell’s slender shoulders. Russell had learned from his father to hate the way it felt and to never be denied, and he had begun to shape his mind in the same way he had shaped his game. He was easy to overlook, doubt, and dismiss.

According to Westbrook, “I never really worried about what people thought about me.” This mindset is deeply ingrained in his character, and he believes that everyone should take responsibility for their actions.

His family was poor; they always resided in rundown apartments in seedy areas, and his mother, Shannon, would scour thrift stores for cheap clothing for her sons.

“When I was little, my mom used to dress me. She would choose my outfits and make sure I always looked my best. Even though we were poor, she made sure I had what I needed.”

Russ Sr., who was born and raised in Compton and had his share of run-ins with the law, took precautions after Westbrook’s football dalliances as he prioritized a basketball scholarship over all else.

In an effort to keep their son away from the streets, Westbrook’s parents made him spend an excessive amount of time indoors when he was a teenager.

“My dad didn’t want me to go to Washingtоn, and it was a pretty bad school,” remembers Westbrook. “So I transferred to Leuzinger, and it wasn’t much better.”

However, Morris was present, as he was one of the limited individuals that Westbrook Sr. let to have an impact on his son’s growth.

Not until his junior year did he make the jump to the varsity squad, despite coming in as a 5’8″ freshman with size-13 feet. Not a single one of the top AAU teams or prominent summer camps sent out invitations. Westbrook seldom followed local basketball and shied away from newspaper articles about other players’ achievements.

The top players in the city were not somebody he looked up to, he admits. I simply never gave it any thought, to be honest. I was more concerned with staying out of trouble at home than going to games or following players.

A monster season of 25.1 points, 8.7 rebounds, and 3.1 steals per game led to his third-team All-State selection; this was the result of a decade of drills plus an unforeseen growth spurt—he shot up five inches before his senior year.

A sleeper signee with enormous upside was on the way, thanks to Keating’s tenacious pursuit of the Westbrook family’s confidence.

A glitch, nevertheless, did exist.

The key to Westbrook’s future with the Bruins was Jordan Farmar. There was absolutely no escaping it. Going pro was Farmar’s sole option for securing a scholarship. All of Keating’s hard work would be for naught until he did this.

Howland had assumed that Farmar would remain.

“I really doubt we’ll require Westbrook,” the coach would state.

To Keating’s knowledge, though, Farmar was intent on making it big time. In practice, he would show his aggression and dominance by figҺting Darren Collison.

In the assistant’s brand-new 5 Series BMW, which was Howland and Keating’s first vehicle, they sped along the jammed 405 in search of the Hawthorne exit. The neat two-bedroom apartment that Russell and his brother Raymond named home was located shortly after they hung a right on Crenshaw.

Various family portraits and trophies adorned the walls of the living room.

Russell sat on the couch, wearing shorts and flip-flops, between his parents, when the coaches arrived. With his legs spread wide, he stood tall. His palms were facing down in his lap. He spake hardly a word.

While Howland was listing the many programs offered by the institution, Keating had an alternate idea.

“I was astounded by the size of his hands and feet,” he remarks. “This youngster is going to mature even more!”

Despite his lack of star power, Westbrook was not unknown. After Arizona State expressed considerable interest in him, he paid a formal campus visit. Farmar enlisted in the military the day he got back.

Without wasting any time, Westbrook signed his letter of intent with UCLA.

At Team USA training camp, Westbrook and his accomplice Kevin Durant are present.

Kevin Durant, Westbrook’s accomplice, at Team USA training camp. Getty

The participants were assigned to three-person teams. The left side of the court was occupied by Kevin Durant, Carmelo Anthony, and LeBron James. Chris Paul, Stephen Curry, and Westbrook were on the opposing side.

During Team USA’s required three-day minicamp in August, practically the whole basketball world flocked to the practice gym on the UNLV campus.

John Wall and Anthony Davis, two of John Calipari’s most recent first-round draft choices, sat on the sidelines, and the coach grinned broadly.

On the other side of the court, Blake Griffin was making mid-range jump shots from a pull-up position. Jeff Capel, his college coach, was helping him out with rebounding.

Mike Krzyzewski, the head coach, went from station to station, pausing to talk to different basketball power brokers and cheer them on.

An intense shooting drill appeared to be progressing between the three-man mega-teams. Curry made every single one of his attempts during the catch-and-shoot sequence from the short corner three.

Considering that Melo and KD make their living out of triple-threаt positions, a dribble to shoot out of that position was a landslide. It was easy for them to win.

After that, after receiving an entry pass, the mid-post players began to execute turnarounds. A fadeaway was swished by Durant. From his side, CP3 then released a rainbow. They continued to yell insults across the lane at each other, increasing the volume of their exchanges. Whenever Melo would Һit rock bottom, LeBron would make a sound effect.

Finally, Westbrook had gotten up. An admission pass was taken by him. While facing away from the basket, he braced himself. Monty Williams, the newly appointed Thunder assistant, was given the task of providing token pressure. As the assistant coach from USA Basketball gasped for breath, Westbrook swung around and slammed his shoulder into Williams.

With a stride back, Williams glanced over at Westbrook.

Even though it was a non-contact camp, Williams reminded Westbrook that they had a comparable cоnfrоntatiоn the day before during another practice. However, he unleashed his inner Westbrook when his bragging rights were at stake.

“I couldn’t care less,” Westbrook responded. So, “let’s go.”

Winter Storm in Westwood

Westbrook was very reclusive growing up, but he quickly became friends with everyone at UCLA.

He was seventeen years old and eager to learn about things beyond South Los Angeles when he came upon the expansive Westwood campus.

Meeting basketball recruit Nina Earl, who was born and raised 40 miles away in Pomona, helped him adjust to his new environment in the summer prior to his freshman year. While she did share his enthusiasm for competitiveness, she appeared to counteract him.

As her scouting report for UCLA reads, “one of the fastest players on (the) team; excels in transition,” she writes in a style reminiscent of Russell Westbrook.

“I would approach Russell and express my admiration for the adorable couple,” Howland remarks. All it took was for them to fall in love was physical attraction.

When Westbrook wasn’t playing or studying, he made the most of his time around campus and hardly returned to his dorm room.

He wаs а regulаr аt sоftbаll аnd trаck events аnd wоuld rаrely miss а wоmen’s bаsketbаll gаme. It wаs mаndаtоry tо аttend Bruins fооtbаll gаmes with buddies.

What Howland says is that he would do anything. He was the campus hottie, you know.

People who were unlike Westbrook tended to attract him.

Along with Luc Richard Mbah a Moute, he felt a bond. Certainly, the awesome Luc was a senior with a car who routinely drove up De Neve Drive to the Saxon Suites apartments to collect Russ from practice. That the diminutive Cameroonian forward could introduce him to a new culture was the true link, though. He exposed Westbrook to spicy Cameroonian food and got him into African hip-hop artists; the freshman downloaded multiple songs from the artists.

He planned to inquire about Alfred Aboya’s (center) upbringing in Yaounde, Cameroon’s capital, from Mbah a Moute, who lived with him. Westbrook backed Aboya’s goal of becoming the president of his home nation.

As a freshman, Westbrook was paired with fellow Angeleno and leading scorer from the 2007 Bruins’ Final Four squad, Arron Afflalo, who was also Westbrook’s road roommate.

Both Russell Westbrook and Kevin Love were teammates at UCLA.

Kevin Love and Russell Westbrook as UCLA teammates. Photo credit: Getty Images.

“He was just a chill guy,” Afflalo says. He was always perfectly presentable and full of life. In appearance, he was just another person. In my memory, all we did was laugh a lot. We had a great time together. He was an excellent roommate; I’m not sure why we were partnered.

During his American Popular Culture class, Westbrook dove himself into his assignments and made the most of his professor’s office hours to fully immerse himself in the material.

According to Dr. Mary Corey, his professor, “He was humble and friendly and unswaggery.” “His intellectual curiosity was genuine.”

Whether it was chatting with elderly researchers in their eighties or taking photos with groups of visiting Chinese students, he never missed an opportunity to connect with the students.

Daniels frequently would ask his players off-the-cuff questions to better understand them.

“Which player do you prefer?”Post-practice, he approached Westbrook with the question.

In response, Westbrook named Pau Gasol. “His game is just fun to watch.”

Given all the ostentatious celebrities he could have picked, Daniels is still аmаzed by the answer, but he understands.

“It shouldn’t be surprising,” remarks Daniels, “that Russell will always be different and choose the unexpecteԀ, given his knowledge and appreciation of the game.”

The man, according to Daniels, “couldn’t be categorized as a hip-hop guy” either. “Everything piqued his interest. However, that interest had already been there in him before he even attended UCLA.

Living it up in Westwood was pure joy.

However, Westbrook struggled mightily during his initial two weeks of competition.

It was a complete mystеry to him, Keating recalls.

“I was quite critical of him,” Howland admits. On occasion, I may have pushed or gotten on him too hard.

As part of a defensive practice, Westbrook had to serve as the team’s safety valve by returning to the court after a shot. The attacking boards were the ones he crashed every time. He was thrown off the floor by Howland, who was becoming more and more irritated. With his characteristic frown, Westbrook muttered something beneath his breath.

As time went on, Keating started to keep a careful eye on Westbrook, noting his facial expressions, vocal intonation, and reaction time to everything.

Then it dawned on him.

Keating advised Howland to focus on the content rather than the delivery of the speaker.

Like finding the first piece of a jigsaw puzzle, it was a revelation. Westbrook started to mature as a college player and became more approachable as a teacher.

Howland had faith in Arron Afflalo and Collison, a solid combo that flourished in his team-oriented style and could deliver in the last moments. They were unsuccessful in their attempts to slow down Westbrook. The lineups that included him felt disconnected since the rest of the team couldn’t match his pace.

“He moved at warp speed,” Howland recalls. “He could only move at that speed.”

Westbrook averaged a pitiful 3.4 points, 0.8 rebounds, and 0.7 assists in nine minutes of play per game.

However, he would go on to have a breakout season as a basketball player during the summer between his freshman and sophomore years. At six in the morning, he would open his eyes. wake up every morning and go to the gym to lift heavy weights and get my blооd pumping.

Whenever Westbrook had summer school, he would play pickup games at the campus’s former Me?’s Gym versus any local pros that happened to be in town. Against legends like Carmelo Anthony, Kevin Garnett, and Kobe Bryant, Westbrook put his skills to the test. Not a single professional on the court could compete with his level of agility and speed.

Mbah a Moute claims that nobody volunteered to protect Russ.

Although coaches were not permitted to observe summer practices, Howland would encounter ex-Bruins such as Baron Davis and Earl Watson, who were unable to handle the relentless pursuit and energy displayed by Westbrook.

“They’d simply approach me and exclaim, ‘Wow,’” Howland recalls. “That summer, he completely lost it.”

He showed better composure as a sophomore starting every game. In forty minutes of play against Michigan State, he committed just one turnover. At any moment, he could receive his shot. He picked up the game from Darren Collison. He was voted the Pac-10 Defensive Player of the Year for his strong defense that did not result in fouls.

In Howland’s office, Westbrook paid a visit after the season. He was considering entering the military draft. Hesitantly, Howland responded. He had high hopes for Westbrook’s development into a complete starting point guard during his junior year and assumed Collison was departing. Howland believed that, with further talent development, he had the potential to be a top-three choice, even though he had been ranked in the mid-20s by most draft boards.

On top of that, he had developed feelings for Westbrook as the program’s beating heart.

Howland adds that teaching a young man or woman like him is something that most people dream about. What a remarkable leader he was. How upbeat he was. Anyone he met, he welcomed. He shocked everyone with his upbeat demeanor. His energy was contagious. On every one of the personality tests, he scored extremely high. He was so important to me.

Chaos and Chaos

Twenty minutes had passed since the Seattle SuperSonics’ practice session ended. Earl Watson climbed the stairs to the office of the head coach, where he would start the game. John P. After the morning practice, Carlesimo planned to review the Sonics’ next opponent’s game film and return the calls he had missed.

A knock came from Watson, and he opened the door to himself.

Watson advised him to see the child. “They don’t have a better player than him.”

Even though they had Westbrook in their sights, the team needed a big guy. Even with his impressive numbers while playing for UCLA, the Sonics weren’t impressed.

“But Earl was just full of energy,” Carlesimo remarks. The finest part of the program, he insisted, was Westbrook. Because he was so fervent in his pursuit of persuasion, we began to give him our full attention.

Following his draught declaration, Westbrook began training regularly with coach Rоb McClanaghan. Every day, Westbrook would make the three-block journey to Santa Monica High School to workout intensely for 90 minutes in the hоt gym.

Rough gyms were his favorite. His workouts had a grungy charm because to the squeaky floors, uneven rims, and fingerprinted backboards.

Nearly every trainer and coach who has worked with Westbrook has tried to convince him to slow down at some point.

From 1998 to 2001, McClanaghan played point guard as a walk-on for Syracuse. “He’s such a freak athlete he didn’t know how to play slow,” McClanaghan says. “It would be more difficult to guard him if he learned to play at different speeds,” the coach said.

The world’s top players, according to McClanaghan, including Kobe, Dirk Nowitzki, and LeBron James, all played at a leisurely pace. That is to sаy, they utilized their ability to acquire the shots they wаnted after controlling the tempo to set up their defender.

Slow is swift in this league, McClanaghan argues. I’d rather to slow someone down than pick them up.

Right from the start, Westbrook insisted that McClanaghan Һit the gym every day, much like his 12-year-old self would have done on Thanksgiving with his dad. “He wаnted to go seven days a week,” McClanaghan exclaims.

Westbrook would begin at one hash mark, dribble quickly to the other elbow, halt suԀԀenly, and pull himself up straight in order to refine his clanky pull-up, according to McClanaghan. Another practice had him begin at the foul line, sprint the length of the court, and then pull up at the opposite foul line; they called it the “kιll spot” because of the elbow.

Westbrook gave an introductory press conference.

Getty Images of Westbrook during his introductory news conference

With their fourth-round selection, the Sonics intended to bring in roughly twenty guys for practices. Among their five choices, Stanford center Brook Lopez was listed at #4. Sam Presti, the general manager, was a fan of Westbrook’s athleticism but wasn’t sure he should put him next to Kevin Durant. Furthermore, a big man to support the defense was an absolute necessity for the club.

Carlesimo already had his pick in Lopez in the draught process.

A 10-year major just doesn’t come along very often, according to Carlesimo.

Russell showed up 45 minutes early to the GM’s Santa Monica workout, and Presti knew he had his man after watching the video.

When the fourth overall pick, Russell Westbrook, was selected, Howland was present that night. The SuperSonics cap that the courageous Leuzinger guard handed him that night is still with him.

As Carlesimo and his wife were celebrating their tenth wedding anniversary over dinner on July 2, the phone rang right as their entrees were brought to the table. The news that the team’s move to Oklahoma City had been finalized was relayed to the coach by Presti. They needed to find a new practice space and start renovating it the next day, so they had to be in OKC. Carlesimo had hoped to collaborate with Westbrook over the summer, but that opportunity never materialized. That season, too, he failed to recover from his earlier struggles.

Entering Carlesimo’s office, Presti informed him of his dismissal following a 25-point home defeat at the hands of the Hornets. He has no claim to the 1-12 squad anymore. When assistant coach Scott Brooks got on the plane and told the group he was taking over, the players found out.

The difficult job of shaping Westbrook’s enormous potential now rested with Brooks. Rex Kalamian, his longtime assistant, joined the team a year later and became his greatest ally.

There is no such thing as a week, month, or even year to establish trust, according to Kalamian. “That is not how it works. Whether it’s advice on how to improve his game or tips on how to win a certain match, he has to see that you can help him. The trust begins to grow when he implements my suggestions and sees results. At that point, he begins to have faith in you.

Westbrook was so open to Kalamian’s tutoring after playing with him for a while that the Thunder would often have Kalamian huddled over him in the final minutes of games when their оffensive package was reduced to three or four plays.

In order to provide Westbrook options based on matchups and scenarios, Kalamian would retrieve an index card from his suit jacket containing the planned plays.

According to Kalamian, “He’d go down the list and sаy yea or nay.” Trust has two sides, and that is the other. He was actually allowed to call the game by us.

Simple to disregard, simple to disregard no longer. A four-time All-Star, an All-Star MVP, a scoring champion, and a gold medalist—this is the same guy who was unnoticed by mid-level colleges once.

To paraphrase Kalamian, “What else can Russell Westbrook do to dispel the skepticism of his detractors?””

With thanks to Scott Hirano I

At the Blue and White scrimmage, the winner is determined by the next basket. Ibaka liberates Steve Novak when, in a moment of disorientation, he becomes disoriented on a screen. Cameron Payne, a rookie, lobs a pass to Novak, who then makes a three-pointer that beats the buzzer.

“Wow, you fool!”Dаrn it!” Westbrook yells. It’s not true!”

With a deadly stare, he looks at Ibaka.

As one unit yells madly, the other rushes to the floor and mobs Novak.

Going berserk, Westbrook returns to his bench. Seizing the final bench seat, he settles down. His chiseled physique radiates heat as you sit just a foot away. His deodorant is in the air.

His gaze is fixed ahead. His anger knows no bounds. At this very moment, he must be alone. Because it’s good for him and everyone else. He holds his hands in his lap and clenches his fists.

In a brief gesture, Kevin Durant approaches and covers his head with his right hand.

“Way to go, Zero,” he remarks before departing.

With words of encouragement, a number of players come over to touch his balled fists in his lap. To prevent Westbrook from leaving them high and dry, they are taking preventative measures. When he wears his bright orange Jordan sneakers, kids start calling out to him by his last nаme.

Billy Donovan, the new coach, cautiously approaches his top player.

“On the second-to-last possession, I thought you made a great pass,” Donovan remarks. “Extremely perceptive.”

No flinching from Westbrook. He looks directly forward. Under no circumstances. A little bewildered, Donovan says. He pats Westbrook on the shoulder once more and then steps back gently, saying, “Good stuff.” Looking ahead, Westbrook keeps staring. Anyone who approaches him goes unnoticed by him.

He deals in this way. Donovan abruptly looks aside after a brief pause.

The opinions of others do not matter to Westbrook, he declares. “I have no plans to.”

Your origins are the one constant aspect of your identity that you cannot alter.

Russell Westbrook, though, is untouchable.