The benefits of canine companionship are myriad. Studies have found dog owners tend to be in better physical shape, more socially adept and have reduced levels of stress and depression. Now new research adds lowered risk for asthma to the list.

The benefits of canine companionship are myriad. Studies have found dog owners tend to be in better physical shape, more socially adept and have reduced levels of stress and depression. Now new research adds lowered risk for asthma to the list.

A study looked at nine different data sets that accounted for more than 1 million children—all born in Sweden between January 2001 and December 2010— and found that those who had pet dogs in the first year of life had a 15 percent lower rate of asthma than those who did not grow up with a dog in the home. The results were consistent even among children who had parents with asthma. The findings of the study—the largest to date that examines the link between pet ownership and asthma—were published Monday in JAMA Pediatrics.

The new research adds some ammo to those who argue for the hygiene hypothesis, which is the theory that living in an environment that is too clean promotes the risk of developing certain conditions, such as asthma.

“If we look at this history, we’ve been living with dogs for a very long time,” says Tove Fall, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Uppsala University in Sweden and a coordinator on the study. “It’s the first pets we had.”

Sweden’s social services and health care system provided a unique opportunity to examine the subject in one comprehensive study on a bigger population. When a child is born in the Sweden, he or she is given a unique identification number, and all medical records, including visits with specialists and prescribed medicines, are kept in a single database.

The country also maintains meticulous records on household data, including information on dog ownership, which has not been used for health research in the past. Swedish dog owners are required by law to register their pet with an identification number.

The authors of the study call the phenomenon the “farming effect,” because other researchers have found that children who grow up on farms are also less likely to develop asthma. An analysis of 39 studies on farming and asthma found children who had early exposure to farm animals, such as cattle and sheep, had a 25 percent lower risk for developing asthma, compared with those who did not grow up on a farm.

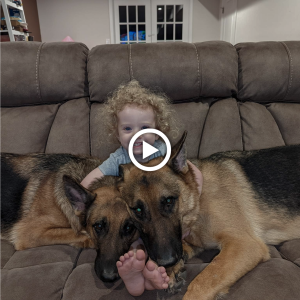

Fall says their findings indicate that having a dog in the household may affect a child’s microbiome, the unique bacterial environment of the gut that is determined by a number of factors, including the air we breathe and the food we eat. Fall wonders if there’s a specific strain of bacteria that’s transmitted from dog to child that makes the latter less prone to asthma. She added that children living in households with dogs probably spend more time outdoors and may be exercising more frequently, both of which could lower their risk for childhood asthma.

But Fall says the new study’s findings are not enough to say definitively that having a dog can help fend off the chronic respiratory condition. Her team hopes to examine the link in more detail. Sweden’s dog registry is highly detailed and includes information on the breed and gender of the dog, which could help them figure out if certain pet qualities offer more protection.

“If you look at dust from a non-dog household, there are nearly no bacterial fragments,” says Fall. “Children that are growing up in a home with a dog are exposed to more microbes. These dog households generally have this lower risk, and we need to find the mechanism behind that.”